Holding the Firearms Industry Accountable for Designing Guns So Easy to Shoot, Even a Toddler Can Do It

10.10.2019

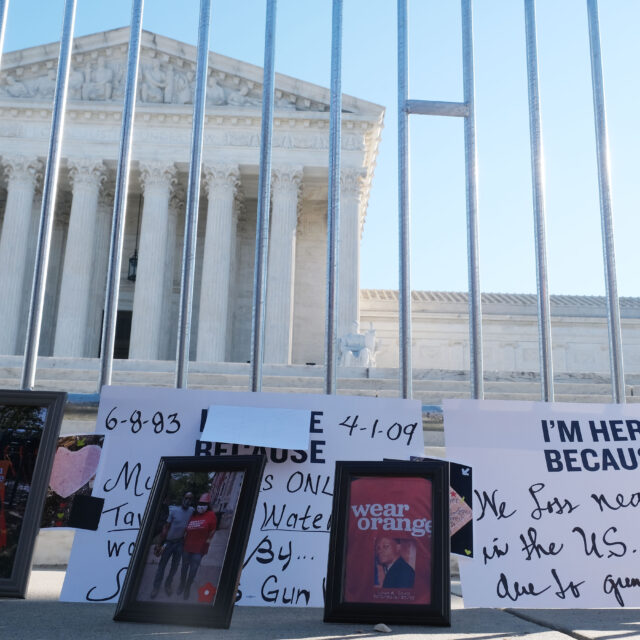

Photo: The Everytown #NotAnAccident Index tracks unintentional shootings by children in the U.S.

A recent Sunday in Texas underscored the shocking regularity with which American children die, or are grievously wounded, in unintentional shootings. In the span of mere hours last month, five Fort Worth-area children were shot in four separate shootings, leaving at least one dead and another clinging to life. Four-year old Truth Albright was one of these victims, shot and killed by his five-year old brother, who police say found a gun in their family home. As of October 2019, Truth was one of at least 10 children to die this year in Texas in an unintentional shooting.

Children like Truth do not need to die this way, and gun makers that design their firearms so that a toddler can shoot them should bear responsibility for their role in these tragic and predictable results. Notwithstanding decades of special treatment that has exempted the firearms industry from product safety regulation and immunized it against many types of legal claims, injured consumers still have at least one powerful tool to incentivize reform: the product defect lawsuit. This is because the federal law that provides immunity to gun makers — the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act — has an exception that allows product defect cases to proceed so long as the discharge of the gun was not a “volitional act that constituted a criminal offense.” Manufacturers are thus unlikely to be immune from lawsuits where they have failed to include safety features to prevent a young child from unintentionally shooting himself or someone else.

The stakes for such a lawsuit are profound. Truth’s death, and Texas’s striking pattern of childhood fatalities, fit into a heartbreaking constellation of unintentional shootings by young children nationwide. Since 2015, there have been at least 1,571 unintentional shootings by children in the United States, resulting in at least 559 deaths and 1,052 injuries. In an average year, nearly 350 American children access a firearm and unintentionally shoot themselves or someone else, and nearly 114 children die as a result. To put these numbers in perspective, around 30 child fatalities over a decade recently prompted a massive recall of Fisher-Price portable cribs. Yet the firearms industry ignores more than three times this number of unintentional child deaths in a single year.

The problem is certainly not that gun makers lack the means or know-how to build a safer gun. Like other industries that rely on low-cost tools to prevent child tragedies (think child-proof medicine bottles), the gun industry has a number of proven, low cost safety mechanisms that can provide a meaningful backstop to secure storage practices. Smith & Wesson, for example, incorporated a grip safety — a lever on the rear of a firearm’s grip that must be depressed for the gun to fire — in a revolver first sold in 1886, more than 130 years ago. “Heavier” triggers — essentially, a stronger spring that makes the trigger harder to pull — can have a similar effect in preventing younger children from discharging a found weapon. Neither of these is a radical redesign. To the contrary, at least one state already requires manufacturers to incorporate a “mechanism which effectively precludes an average five year old child from operating the handgun” through things like a minimum 10-pound trigger pull, grip safety, or similar device.

Other features can meaningfully improve safety for older children and adults. These include magazine disconnects (which prevent semi-automatic handguns from firing once the magazine has been removed, even if a round remains in the chamber) and indicators that clearly show whether a round is chambered. Features like these might have prevented the unintentional shooting of Edward Hatcher, age 17, killed by a friend who thought he had unloaded the gun by removing its magazine. They might also have prevented the death of 16-year-old Desean Mitchell, who was killed when a friend tried to “dry fire” a handgun the boys had found, not realizing it had a round in the chamber.

More advanced safety tools, such as user-authorized technology (e.g., biometric readers and radio frequency identification (RFID) tags built into handgun grips) is also rapidly maturing, though the firearms industry has actively resisted its adoption, claiming that the technology is unreliable. But as described in a 2016 DOJ report, at least three smaller manufacturers have incorporated these technologies into “commercializable” firearms. Unfortunately, gun dealers that have attempted to sell “smart” guns have been bullied into removing them from their inventory.

So if these lifesaving technologies exist, why don’t they come standard? The problem is that gun makers lack the incentives. As the American Outdoor Brand Corporation (the parent company of Smith & Wesson) recently explained, it “has not seen any meaningful increase in the Company’s operating, capital or regulatory costs as a result of firearms-related violence.” Indeed, the firearms industry faces little meaningful regulatory oversight in the design of its products: guns, ammunition, and ammunition components are all exempt from regulation by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). And only a few states mandate safety features like chamber load indicators or magazine disconnects. As a result, even though government regulation has brought about critical safety features in other consumer products — like airbags in cars, and child-resistant drug packaging — it appears unlikely to have a similar effect on guns anytime soon.

To fill this regulatory gap, injured consumers have a powerful tool to incentivize safer guns: product liability lawsuits. Like regulatory oversight, the power of product liability to reform dangerous product design is hard to overstate. A single $125 million jury verdict in California in the late 1970s pushed Ford to relocate the gas tank in its Pinto hatchback to reduce the risk of explosion in a rear-end collision. Lawsuits in the 1980s and 90s by the families of children burned by disposable lighters led to a 1993 CPSC rule mandating the introduction of child-resistant mechanisms. In the 1990s, a series of lawsuits over “tread separation” in Bridgestone/Firestone tires led to recalls and the passage of federal reporting obligations designed to facilitate the early detection of safety problems. In these cases and many others, litigation by injured consumers became the impetus for safer product design.

Of course, federal and state gun industry immunity laws place a significant hurdle in the way of civil lawsuits against gun manufacturers. But in some instances, family members of children harmed in unintentional shootings may be able to hold the manufacturer accountable in court for unsafe product design, creating powerful incentives for reform. Because young children lack the mental capacity to commit a “volitional act that constitute[s] a criminal offense,” an unintentional shooting by a young child should not trigger the federal immunity law, allowing a product defect claim to proceed. Even a single such case could provide a clear path to hold the firearms industry accountable for failing to build lifesaving features into its guns. It would also give gun makers reason to invest in technologies to save the lives of future children just like Truth.