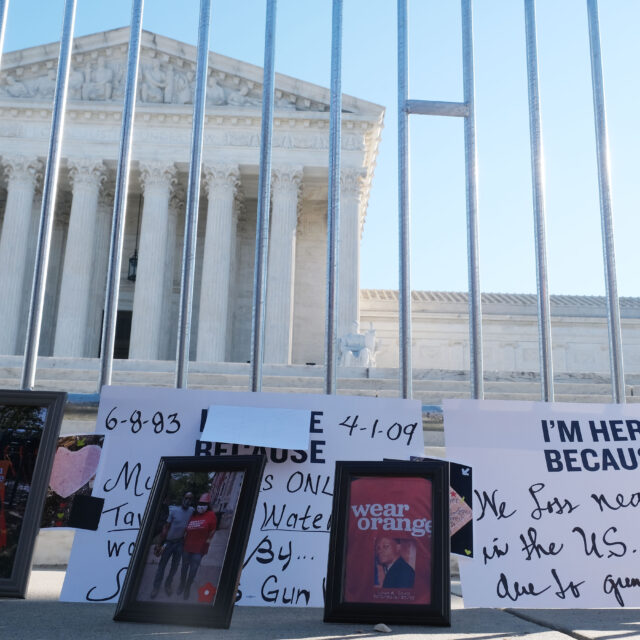

The Second Amendment Does Not Require Officials to Give Gun Stores Special Treatment During Coronavirus Closures

4.1.2020

States and localities all over the country have ordered businesses to close as part of broad efforts to minimize person-to-person contact and slow the spread of COVID-19. Not all of those orders apply to firearms and ammunition dealers, but several do. Litigation over a Pennsylvania order has already resulted in one judicial decision. Lawsuits filed by the NRA and its affiliates are also pending in New Jersey and California; additional challenges may follow.

The gun lobby claims that including gun stores in these closure orders impermissibly treats the Second Amendment as a “second-class right.” But the truth is just the opposite. What the NRA and other gun groups are seeking instead is for Second Amendment rights to become super-rights, receiving a level of protection no other constitutional right enjoys.

As explained in Everytown Law’s memorandum, and summarized below, the central claim in these legal challenges — that the Second Amendment requires that gun stores be singled out for special treatment and be allowed to remain open even in the face of the most severe public-health crisis this country has faced in over 100 years — is legally flawed and should be rejected by the courts.

The critical point that these gun lobby lawsuits overlook is that the emergency closure orders are not specifically targeted at guns or gun stores, just as they are not specifically targeted at bookstores, political rallies, houses of worship, marriage license bureaus, or other locations that are being ordered closed notwithstanding their connection to constitutional rights. They are instead examples of the sorts of generally-applicable rules that courts have held do not violate a constitutional right despite placing burdens on that right.

For example, in an important decision concerning freedom of speech, the Supreme Court upheld the application of a state’s “public health regulation of general application” to close a bookstore found to be public-health nuisance. While the burden on speech was significant, as the bookstore was forced to shut its doors for a year, that did not change the result. Because the law at issue was directed at conduct “having nothing to do with books or other expressive activity,” the First Amendment simply was not implicated. Similarly, the Supreme Court has held that incidental burdens on the free exercise of religion — even severe ones prohibiting conduct central to an individual’s faith — cannot relieve one of the obligation to comply with a law that is “not specifically directed at . . . religious practice.”

Although the Supreme Court has not yet applied these principles in a Second Amendment case, opinions by two influential federal appellate-court judges support that application. In one case challenging a zoning provision that prohibited firearms sales near specified locations, a federal appellate judge explained that a “measure of general application” that affects “retail stores of any kind,” and not just gun stores, would not raise a Second Amendment issue. In another case, a judge — interpreting the U.S. Supreme Court’s approval of “conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms” — similarly wrote that “rules of general applicability do not violate the Second Amendment just because they place conditions on . . . sales of handguns used for self-defense,” explaining that “[w]e accept such restrictions on our rights — including our fundamental rights to speak, publish, and exercise our religion — because laws of general applicability cover a broad range of activities and, hence, must have broad, popular acceptance and support.”

There is no question that the emergency closure orders are “valid and neutral law[s] of general applicability,” regardless of their impact on firearms retailers. New York, for example, has closed not only gun stores but also, to name a few, bookstores, marriage license bureaus, social clubs, and performing arts centers — all of which places notable burdens on constitutional rights. Because suppressing the exercise of Second Amendment rights (or of any other right) is not the object of the closure orders, they remain neutral, generally applicable, and thus constitutional.

These points are a complete answer to allegations that states and localities are imposing improper burdens on Second Amendment rights. But it is also worth noting that opponents of the closure orders have significantly overstated those burdens.

To begin, the right recognized in District of Columbia v. Heller is an individual right of law-abiding, responsible citizens to keep and bear certain firearms (such as handguns) in the home for self-defense. It “does not confer a freestanding right on commercial proprietors to sell firearms.” And, to the extent that individuals who do not own or possess guns assert that these orders infringe their right to keep and bear arms because they want to buy a gun but currently cannot, it is important to bear in mind that the Second Amendment does not guarantee a right to acquire a gun immediately, at any time, on demand. The Supreme Court affirmed in Hellerthat “laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms” are constitutional. And, since Heller,courts have upheld background checks, waiting periods, licensing laws, and training requirements as consistent with the Second Amendment, even though they bring with them delays on immediate acquisition.

Those limitations on the ability to purchase a gun on demand are in place to protect public safety — to keep guns out of the hands of dangerous individuals, to ensure that a gun is not purchased and used immediately in an impulsive act of violence or self-harm, and to further the safe and responsible use of firearms. The same is true of orders temporarily closing retail commercial businesses: they are in place to protect public health and safety in the face of the unique and unprecedented circumstances of the current crisis. Given that it is lawful to temporarily delay firearm purchases in the ways described above, it follows that state and local officials do not violate the law by temporarily delaying such activity as part of a general suspension of vast swaths of retail and other commercial businesses to address an urgent public-safety crisis.

Finally, the seriousness of the COVID-19 pandemic weighs heavily in favor of upholding the current closure orders. Courts repeatedly have recognized that the existence of a public-health or similar emergency is vitally important in considering the weight of the public interest in the context of an individual’s desire to exercise constitutional rights.

Throughout our nation’s history, the judiciary has reaffirmed that states have broad police powers to protect public health. Being in close contact with others is precisely what will make the COVID-19 emergency worse, and that close contact is what states and localities are trying to minimize in ordering thousands of retail businesses to close. Including gun stores within those neutral and generally-applicable closure orders is entirely constitutional.

NOTE: The legal arguments set forth here and in the linked memorandum reflect the opinions of Everytown Law, are presented for informational purposes only and are not legal advice from Everytown Law. No court has decided the precise issues discussed. Public officials should consult with their own counsel about these issues and arguments and how they might apply depending on specific facts and circumstances. The outcome of any litigation around these issues is unpredictable.